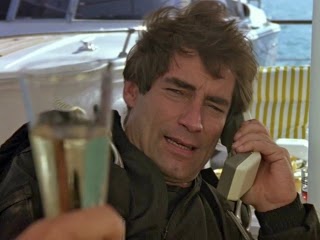

Justice League: The

Flashpoint Paradox (2013) – The Flash (Justin Chambers) wakes up in a world

he doesn’t recognize, where Aquaman and Wonder Woman are at war, where Thomas

Wayne is Batman (Kevin McKidd); suspecting his nemesis Professor Zoom (C.

Thomas Howell), Flash sets out to restore his powers and the world he knows

before this one destroys itself in war. While

I greatly enjoyed the original comics by Geoff Johns and Andy Kubert, I felt a

little underwhelmed by the film adaptation for two big reasons: its ambition

and its animation. In terms of ambition,

this 80-minute film tries to embrace the scope of the entire comic series, a

summer crossover spanning more than sixty single issues. Add to that the film’s attempt to adapt a

Flash-centric comic into a Justice League adventure, and you’re looking at a

heavy dose of Easter eggs that don’t really advance the plot. Having said that, the way that the filmmakers

recount the brilliant Batman: Knight of

Vengeance (by Brian Azzarello and Eduardo Risso) in about ten seconds is

genius, highlighting the clever twist Azzarello brought to the alternate-world

story. My second grievance is the

animation style, much looser and anime-inflected than some of the more polished

recent entries from the DC Universe Animated Original Movies studio. While this aesthetic is probably appealing to

some, it feels choppy and bargain-bin, far from the caliber I’d expect from the

DC studio. It’s a diverting enough film,

told capably if briskly with a few memorable sequences, but it’s so incredibly

dark (one character is shot in the head, in extremely

graphic detail, more than warranting its PG-13 rating) and so poorly animated

that it’s hard to imagine anyone who isn’t a diehard DC devotee lapping this

one up.

Justice League: The

Flashpoint Paradox (2013) – The Flash (Justin Chambers) wakes up in a world

he doesn’t recognize, where Aquaman and Wonder Woman are at war, where Thomas

Wayne is Batman (Kevin McKidd); suspecting his nemesis Professor Zoom (C.

Thomas Howell), Flash sets out to restore his powers and the world he knows

before this one destroys itself in war. While

I greatly enjoyed the original comics by Geoff Johns and Andy Kubert, I felt a

little underwhelmed by the film adaptation for two big reasons: its ambition

and its animation. In terms of ambition,

this 80-minute film tries to embrace the scope of the entire comic series, a

summer crossover spanning more than sixty single issues. Add to that the film’s attempt to adapt a

Flash-centric comic into a Justice League adventure, and you’re looking at a

heavy dose of Easter eggs that don’t really advance the plot. Having said that, the way that the filmmakers

recount the brilliant Batman: Knight of

Vengeance (by Brian Azzarello and Eduardo Risso) in about ten seconds is

genius, highlighting the clever twist Azzarello brought to the alternate-world

story. My second grievance is the

animation style, much looser and anime-inflected than some of the more polished

recent entries from the DC Universe Animated Original Movies studio. While this aesthetic is probably appealing to

some, it feels choppy and bargain-bin, far from the caliber I’d expect from the

DC studio. It’s a diverting enough film,

told capably if briskly with a few memorable sequences, but it’s so incredibly

dark (one character is shot in the head, in extremely

graphic detail, more than warranting its PG-13 rating) and so poorly animated

that it’s hard to imagine anyone who isn’t a diehard DC devotee lapping this

one up. Star Wars: The Clone

Wars (2008) – Hard to believe I’ve never reviewed a Star Wars film on here, isn’t it?

This is a bit of an odd place to start, a midquel made three years after

Episode III but set before it as a

backdoor pilot for a television series of the same name. A classic gripe about the prequel trilogy is

that we never see the much-heralded Clone Wars, which begin in Episode II’s climax and end in Episode III; this film and its progeny

attempt to bridge that gap. In 3D

modeling reminiscent of a video game, Anakin Skywalker (Matt Lanter) and

Obi-Wan Kenobi (James Arnold Taylor) defend the Republic from the Separatist

forces that threaten to tear it apart; amid the chaos of war, Anakin takes on a

Padawan, young Ahsoka Tano (Ashley Eckstein), as they liberate planets and the

kidnapped son of Jabba the Hutt. Though I’ve

heard good things about the television show that followed, the fact is that The Clone Wars is not much better than

the prequel trilogy that preceded it – but it is better by virtue of stronger

dialogue and better characterization, safely away from the pen of George

Lucas. The real gem is the character of

Ahsoka; the thought of Anakin taking on an apprentice is not exactly appealing,

but Eckstein gives the character a spirited persona with an infectious

eagerness to master the Jedi ways. If I

end up watching the show, it’ll largely be to see what comes of her

character. Unfortunately, while The Clone Wars improves on Lucas’s apparent

inability to write character with personalities, it suffers from the prequel

trilogy’s over-cluttered nature, with way too many subplots,

double/triple-crosses, and characters dropped in solely for fan service. For example, I’ll never really complain about

Samuel L. Jackson’s presence, but his voiceover as Mace Windu accomplishes

literally nothing. Ditto for the

surprisingly offensive homophobia in the effete character of Ziro the Hutt

(think Jabba by way of Truman Capote in garish drag). If such a thing exists, The Clone Wars is a misstep in the right direction, rectifying a

few of the prequel trilogy’s errors but committing a few of its own.

Star Wars: The Clone

Wars (2008) – Hard to believe I’ve never reviewed a Star Wars film on here, isn’t it?

This is a bit of an odd place to start, a midquel made three years after

Episode III but set before it as a

backdoor pilot for a television series of the same name. A classic gripe about the prequel trilogy is

that we never see the much-heralded Clone Wars, which begin in Episode II’s climax and end in Episode III; this film and its progeny

attempt to bridge that gap. In 3D

modeling reminiscent of a video game, Anakin Skywalker (Matt Lanter) and

Obi-Wan Kenobi (James Arnold Taylor) defend the Republic from the Separatist

forces that threaten to tear it apart; amid the chaos of war, Anakin takes on a

Padawan, young Ahsoka Tano (Ashley Eckstein), as they liberate planets and the

kidnapped son of Jabba the Hutt. Though I’ve

heard good things about the television show that followed, the fact is that The Clone Wars is not much better than

the prequel trilogy that preceded it – but it is better by virtue of stronger

dialogue and better characterization, safely away from the pen of George

Lucas. The real gem is the character of

Ahsoka; the thought of Anakin taking on an apprentice is not exactly appealing,

but Eckstein gives the character a spirited persona with an infectious

eagerness to master the Jedi ways. If I

end up watching the show, it’ll largely be to see what comes of her

character. Unfortunately, while The Clone Wars improves on Lucas’s apparent

inability to write character with personalities, it suffers from the prequel

trilogy’s over-cluttered nature, with way too many subplots,

double/triple-crosses, and characters dropped in solely for fan service. For example, I’ll never really complain about

Samuel L. Jackson’s presence, but his voiceover as Mace Windu accomplishes

literally nothing. Ditto for the

surprisingly offensive homophobia in the effete character of Ziro the Hutt

(think Jabba by way of Truman Capote in garish drag). If such a thing exists, The Clone Wars is a misstep in the right direction, rectifying a

few of the prequel trilogy’s errors but committing a few of its own.That does it for this week’s edition of “Monday at the Movies.” We’ll see you here next week!